For many years, treating a heart valve condition meant open-heart surgery, large incisions, and a long recovery. I’ve seen how daunting this can feel for patients. Today, TAVR, or Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement, offers a less invasive way to restore valve function. Many patients are walking the very next day, with significantly shorter hospital stays and faster recoveries.

This guide explains what TAVR is, who can benefit, what to expect during the procedure, and how to prepare. I’ve also included a full FAQ and checklist to help you feel confident every step of the way.

What is TAVR? A simple explanation

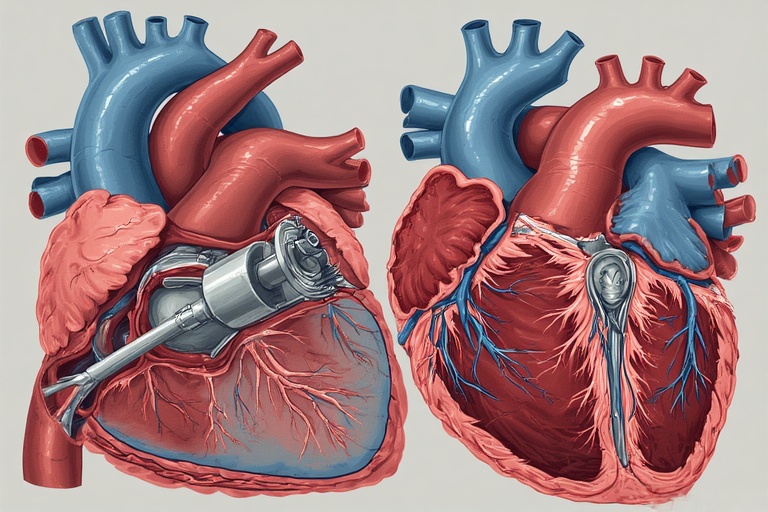

TAVR, or transcatheter aortic valve replacement, is a minimally invasive procedure that replaces a damaged aortic valve without the need for open-heart surgery. Using a thin tube called a catheter, we guide a new valve to the heart through a blood vessel, usually in the leg. Once in place, the new valve immediately restores proper blood flow.

TAVR is most commonly used for patients with severe aortic stenosis. In this condition, the aortic valve becomes stiff and narrow, making it harder for blood to leave the heart and reach the rest of the body. Left untreated, it can cause chest pain, shortness of breath, fainting, or even heart failure.

When TAVR was first introduced, it was primarily offered to patients who were considered too high-risk for open-heart surgery. Today, advances in technology have expanded its use, making it a viable option for many patients, including those at lower risk. Compared with traditional surgery, TAVR often results in shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and noticeable improvements in daily life.

Who is a candidate for TAVR? How doctors decide

TAVR is usually considered for patients with severe aortic stenosis, particularly when symptoms interfere with everyday life. Shortness of breath, chest discomfort, fainting spells, or persistent fatigue are some of the most common warning signs.

To confirm severity, we rely on an echocardiogram. This test measures how well the valve opens and closes, the pressure across the valve, and the size of the valve opening. These details show us how restricted blood flow is and help guide the treatment plan. Patients with significant narrowing and clear symptoms are often the ones who benefit most from TAVR.

Risk scores and frailty

Before recommending TAVR, your overall health and surgical risk are carefully assessed. Scoring systems such as the STS (Society of Thoracic Surgeons) score or EuroSCORE help estimate the potential risks of open-heart surgery. Frailty of the patient is also evaluated, which means looking at strength, mobility, and physical reserve. Sometimes even with serious valve disease, patients may face higher risks if they are frail or have other conditions.

This is why regular heart screenings are so important so that problems can be detected earlier, before they become severe.

The CT scan that decides everything

A detailed CT scan of the heart and blood vessels is critical for planning TAVR. The scan measures the size and shape of the aortic valve opening (annulus), identifies calcium deposits, and determines the safest pathway for the catheter to reach the heart. For example, if the annulus measures 24 millimeters across, doctors choose a replacement valve that fits precisely to prevent leaks. The scan also helps decide whether the catheter can travel through the leg arteries or if an alternative route is needed. This imaging ensures the procedure is both safe and effective.

TAVR vs Open Surgery (SAVR): What the numbers mean for you

Short-term outcomes (mortality, stroke, LOS)

Both transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) have shown excellent short-term results, but there are some differences worth noting.

Recent studies show that for patients at intermediate to high surgical risk, the 30-day survival rate after TAVR is very high, with mortality rates around 2–4%. This is slightly lower than what is typically seen with SAVR in similar groups.

The risk of stroke after either procedure is similar, usually around 2–3%, and in some studies, TAVR shows a small advantage.

One of the clearest differences is in recovery time. Hospital stays after TAVR average 2–5 days, compared to 7–10 days for SAVR. This shorter stay reflects both the minimally invasive nature of TAVR and the faster return to daily activities for many patients.

Medium and longer-term outcomes (quality of life, 5–10 year data)

In the medium and long term, both TAVR and SAVR provide meaningful improvements in quality of life. Patients typically notice relief from symptoms, better functional status, and improved exercise tolerance.

Clinical trials show that people who undergo TAVR often experience a faster boost in quality-of-life scores within the first 1–6 months. By about one year, however, outcomes between TAVR and SAVR usually level out.

When it comes to survival, the results are also encouraging. For intermediate-risk patients, five-year survival rates are now similar for both procedures, averaging around 70–75%. Ten-year data, available mostly from surgical cohorts, suggest durable survival and strong valve performance.

One area where differences remain is paravalvular leak—a condition where blood flows around the new valve instead of through it. This has historically been more common with TAVR, though newer-generation valves have significantly narrowed this gap.

Ultimately, the decision between TAVR and SAVR depends on age, overall health, and recovery priorities. TAVR often provides earlier recovery benefits, while SAVR may offer reassurance in terms of long-term durability. A personalized discussion with your heart team is essential to find the option that best matches your goals and health profile.

Durability & lifetime planning for younger patients

For younger patients, the conversation around valve replacement goes beyond immediate recovery as you also have to consider durability and long-term planning.

Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) has a well-established track record, with valves often lasting 15–20 years. TAVR valves, though newer, show promising durability in the mid-term, with strong performance documented up to 8–10 years so far.

When a TAVR valve eventually wears out, it is sometimes possible to place a new valve inside the old one. This procedure is called valve-in-valve TAVR (TAV-in-TAV). While this option can extend valve function, it also comes with anatomical and technical considerations, and not every patient will be an ideal candidate for multiple valve-in-valve procedures.

For this reason, treatment decisions for younger patients need to consider:

- The likelihood of future interventions

- How many times a valve-in-valve approach might be possible

- The impact on lifestyle and long-term heart health

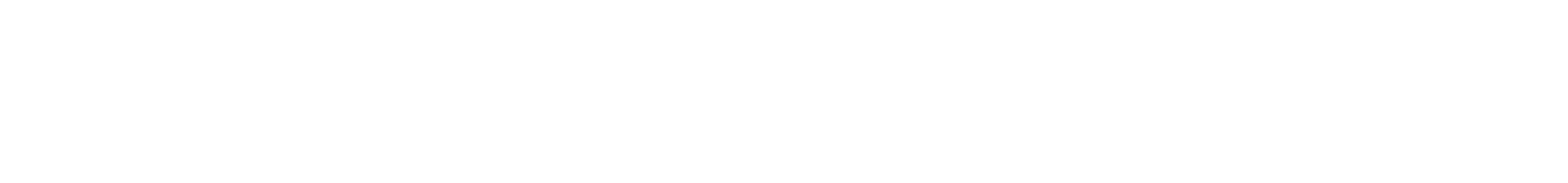

How the TAVR procedure works — step by step

TAVR is carefully planned and performed by a heart team so the procedure is precise and recovery is smooth. Here’s what the day typically looks like.

- Pre-procedure checks

You’ll meet the team, review consent, and have final vitals, labs, and imaging verified. Medications are confirmed and adjusted if needed. - Anesthesia and monitoring

Most procedures use local anesthesia with light sedation; some patients receive general anesthesia. Heart rhythm, blood pressure, and oxygen are monitored continuously. An ultrasound probe (echocardiography) and X-ray guidance (fluoroscopy) help the team see the valve in real time. - Vascular access

The team places small tubes (sheaths) into the access vessel and gives blood thinners to prevent clots. A temporary pacing wire may be positioned to help stabilize the heart during valve deployment. - Crossing the aortic valve

A soft wire and catheter are guided across the narrowed valve. The replacement valve—mounted on a delivery system—travels over this wire to the correct spot. - Positioning and deployment

Under echo and X-ray guidance, the new valve is aligned within the old valve.

• Balloon-expandable valves are opened with a brief balloon inflation (often during rapid pacing).

• Self-expanding valves are released gradually and fine-tuned for position.

The new valve begins working immediately. - Assessment and optimization

The team checks valve function, blood flow, and any leak around the edges (paravalvular leak). If needed, a quick balloon inflation fine-tunes the seal. Pressures are re-measured to confirm improved flow. - Device removal and closure

Catheters and wires are removed, and the access site is closed with sutures or closure devices. Dressings are applied, and circulation to the limb is checked. - Recovery and mobilization

You’ll spend several hours in a monitored unit. Most patients sit up and walk the same day or the next morning. Hospital stays are usually short, and discharge instructions cover medications, wound care, activity, and follow-up.

Access routes (how we reach the heart)

Transfemoral (most common)

The catheter enters through a blood vessel in the groin and is guided to the heart. This route is the least invasive and usually offers the fastest recovery.

Transapical

A small incision is made on the left chest, and the catheter enters directly through the tip (apex) of the heart. This is considered when the leg arteries are not suitable.

Transcarotid

The carotid artery in the neck provides a straight, controlled path to the aortic valve. It’s an option for select patients when transfemoral access isn’t ideal.

Risks & Complications — what to watch for?

Like any procedure, TAVR carries risks, though serious complications are relatively uncommon. Stroke occurs in about 2–3% of patients, often immediately around the procedure. Vascular complications, such as bleeding or damage to the blood vessel used for access, occur in roughly 5–8% of cases, more often with smaller or tortuous arteries.

Paravalvular leak, where blood leaks around the new valve, is seen in 5–10% of patients with modern valves, usually mild and well-tolerated. Your care team minimizes these risks using careful imaging, advanced valve technology, and meticulous technique, helping most patients leave the hospital safely.

Risk factors for complications include pre-existing vascular disease, valve calcification, and comorbid conditions like high cholesterol or diabetes. Learn more about these contributors here: [Cholesterol’s Role in Heart Health…] and [The Link Between Diabetes and Heart Health…].

Conduction issues & pacemaker risk — who is at higher risk and why

TAVR can affect the heart’s electrical system, sometimes causing arrhythmias or the need for a permanent pacemaker. About 10–15% of patients require a pacemaker after TAVR, though newer valve designs have reduced this risk. Patients with pre-existing conduction delays, right bundle branch block, or heavily calcified valves are at higher risk. Your team monitors your heart rhythm during and after the procedure and is prepared to intervene quickly if needed, keeping you safe and avoiding long-term complications.

Special anatomies: bicuspid valves and pure aortic regurgitation

Certain valve anatomies make TAVR more complex. Bicuspid valves, which have two leaflets instead of three, and pure aortic regurgitation, where the valve leaks without narrowing, pose challenges for precise valve placement and long-term sealing. These cases may carry higher risks of paravalvular leak or valve malposition. Your heart team evaluates your imaging carefully to decide if TAVR is suitable or if surgical options are safer, ensuring the procedure fits your unique anatomy and maximizes success.

Recovery timeline: day-by-day then week-by-week

First 72 hours in hospital (mobility, lines, discharge criteria)

After TAVR, patients usually spend 1–3 days in the hospital. You’ll have monitors, IV lines, and sometimes a temporary urinary catheter. Nurses and therapists encourage early mobility—often sitting up the same day and walking short distances the next. Pain is typically mild and managed with oral medication. Discharge criteria include stable heart rhythm, good wound healing, and ability to move safely. Many patients report, “I was up and walking almost immediately—it felt reassuring.” Your care team tailors recovery to your specific procedure and overall health.

Week 1–2 (wound care, driving, light activity)

At home, focus on gentle activity and wound care. Keep the groin or chest incision clean and dry, watching for redness or swelling. Light household tasks are fine, but avoid heavy lifting or strenuous exercise. Driving is generally paused for at least one week or until cleared by your doctor. Most patients feel more comfortable moving around daily and sleeping without discomfort.

Weeks 3–6 (cardiac rehab, return to work/exercise progression)

During weeks 3–6, many patients start cardiac rehab, which helps strengthen the heart and improve endurance. Gradually increase walking and light exercise, following your rehab team’s guidance. Returning to work is often possible depending on your job and energy levels. By six weeks, most patients resume most normal activities, with continued monitoring at follow-up visits.

Medications after TAVR & follow-up care

Typical antithrombotic strategies (aspirin vs dual therapy)

After TAVR, most patients take aspirin long-term, sometimes combined with a short course of clopidogrel (dual therapy) for a few months. The exact plan varies based on your risk of bleeding or clotting. Your cardiologist will create a personalized regimen, balancing protection against clot formation with safety.

Dental procedures, endocarditis risk, MRI guidance

Good dental hygiene is essential because infection in the mouth can rarely affect the heart valve. Some procedures may require antibiotic prophylaxis. TAVR valves are generally MRI-compatible, but always check with your care team first. Routine follow-ups monitor valve function and heart rhythm to prevent complications.

Costs, length of stay & what affects your bill

Most TAVR patients stay 1–5 days, depending on procedure complexity and recovery speed. Cost can vary with factors like need for a pacemaker, stroke care, vascular repairs, or regional hospital differences. Your hospital can provide an estimate and itemized charges. Always ask about coverage and anticipated costs in advance to plan effectively.

Special cases: bicuspid valves, pure AR, and younger patients

Bicuspid valves (two leaflets) can make TAVR placement more challenging, and pure aortic regurgitation may require specialized devices. Younger patients require careful lifetime planning, including the potential need for future interventions like valve-in-valve procedures. A Heart Team discussion ensures your approach balances durability, anatomy, and long-term health.

Reference: Understanding How Inherited Mutations Affect Your Heart and Blood Health

FAQ

How long does it take to recover after TAVR?

Most patients return to light activity within 1–2 weeks and resume normal daily activities by 4–6 weeks. Cardiac rehab can accelerate recovery and improve stamina.

Is TAVR better than open heart surgery for aortic stenosis?

TAVR is less invasive, with shorter hospital stays and faster early recovery. Long-term outcomes are comparable in intermediate- and high-risk patients, though valve durability should be considered in younger patients.

How long do TAVR valves last?

Modern TAVR valves show reliable function for 8–10 years, with emerging evidence suggesting durability may extend further. Surgical valves may last longer, typically 15–20 years.

Will I need blood thinners after TAVR?

Most patients take aspirin indefinitely. Some may also receive short-term clopidogrel (dual therapy) depending on their clotting and bleeding risk. Your cardiologist tailors this to your needs.

What is the risk of needing a pacemaker after TAVR?

Approximately 10–15% of patients require a pacemaker, higher in those with pre-existing conduction delays or calcified valves. Monitoring during and after the procedure helps manage this risk.

Is TAVR safe for bicuspid valves or pure AR?

TAVR is possible but more technically challenging in these anatomies. Specialized devices and careful planning by a Heart Team are essential for safe outcomes.

Can I drive after TAVR?

Driving is typically paused for 1–2 weeks or until your doctor clears you, depending on mobility, medications, and energy levels.

Can I get an MRI after TAVR?

Most modern TAVR valves are MRI-compatible. Always check with your cardiologist before imaging to confirm safety.